CMMC Level 1 Requirements Explained (2025): Plain-English Guide for SMB Defense Contractors

If you’re a small defense contractor, you’ve probably heard about the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC). Level 1 is the entry point. It covers 15 basic safeguarding practices drawn from federal regulation (FAR 52.204-21) and designed to protect Federal Contract Information (FCI), the government data you handle while delivering a contract.

The problem? The official requirements are written in legalistic, technical language. If you’re not a security expert, it’s hard to know what they really mean for your business.

Understanding CMMC Level 1 in plain English helps your business protect contracts, avoid costly surprises, and reduce the burden of compliance management. By breaking down requirements into everyday language and IT practice, you can make better decisions. With this information you can avoid hiring a full compliance team before you’re ready, or gain the knowledge to understand what a compliance team is doing if you do decide to work with one.

This guide breaks down each of the 15 CMMC Level 1 practices in plain English, with:

- Everyday analogies so the concepts make sense

- A translation into IT terms so you understand how it applies to your systems

- Real-life small-business examples

- The kind of evidence assessors expect

- Common mistakes to avoid

This is a high-level guide, designed to help you understand CMMC Level 1 without drowning in jargon. It doesn’t include every IT configuration detail you’d need to fully compliance-proof your environment. That’s where expert help comes in. Working with a partner like Opsfolio CaaS means these practices aren’t just explained, but actually implemented, monitored, and documented on your behalf. You get clarity here, and a turnkey path to compliance when you’re ready.

Table of Contents

- Limit Access to Authorized Users (AC.L1-b.1.i)

- Limit Access by Transaction and Function (AC.L1-b.1.ii)

- Verify and Control External Connections (AC.L1-b.1.iii)

- Control Public Information (AC.L1-b.1.iv)

- Identify Users, Processes, and Devices (IA.L1-b.1.v)

- Authenticate Users, Processes, and Devices (IA.L1-b.1.vi)

- Sanitize or Destroy Media Containing FCI (MP.L1-b.1.vii)

- Limit Physical Access to Systems and Equipment (PE.L1-b.1.viii)

- Manage Visitors and Physical Access Devices (PE.L1-b.1.ix)

- Monitor and Protect Network Boundaries (SC.L1-b.1.x)

- Separate Public-Facing Systems from Internal Networks (SC.L1-b.1.xi)

- Identify, Report, and Correct Flaws (SI.L1-b.1.xii)

- Protect Against Malicious Code (SI.L1-b.1.xiii)

- Keep Malicious Code Protection Updated (SI.L1-b.1.xiv)

- Perform System & File Scanning (SI.L1-b.1.xv)

- Building a Strong Foundation with Level 1

15 Practices at a Glance

| Practice Family | Practices | Why It’s Important |

|---|---|---|

| 🔑 Access Control (AC) | • Authorized Access Control • Transaction & Function Control • External Connections • Control Public Information | Controls who can get in, what they can do, and how information leaves your systems — the foundation of protecting FCI from both mistakes and attackers. |

| 🆔 Identification & Authentication (IA) | • Identification • Authentication | Ensures every user, device, and process is uniquely identified and verified before access — stopping impostors and shared “mystery accounts.” |

| 💾 Media Protection (MP) | • Media Disposal | Prevents sensitive contract data from leaking through discarded hard drives, USBs, or copiers. |

| 🏢 Physical Protection (PE) | • Limit Physical Access • Manage Visitors & Physical Access Devices | Locks down the physical environment — keeping servers, laptops, and contract data safe from theft, tampering, or unsupervised visitors. |

| 🌐 System & Communications Protection (SC) | • Boundary Protection • Public-Access System Separation | Protects the “edges” of your network — firewalls, VPNs, and DMZs — so outside threats don’t cross into sensitive internal systems. |

| 🛡️ System & Information Integrity (SI) | • Flaw Remediation • Malicious Code Protection • Update Malicious Code Protection • System & File Scanning | Keeps systems healthy: patching flaws, blocking malware, updating defenses, and scanning regularly to catch what slips through. |

Let’s get started.

Limit Access to Authorized Users (AC.L1-b.1.i)

What it means and why it matters:

Imagine your company network like a secure office building. You wouldn’t give out master keys to random visitors or let former employees keep theirs after leaving. You’d track who is allowed inside, issue them keys or badges, and make sure those keys are collected when they no longer belong. This control is the digital version of that practice: only people, devices, and automated processes that you’ve explicitly approved should be able to access your information systems.

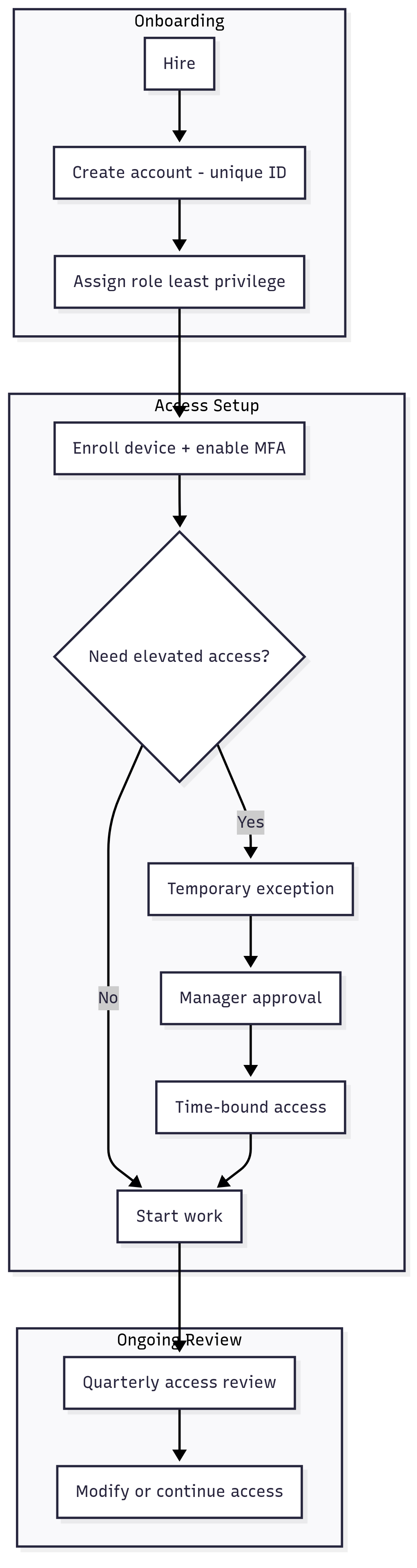

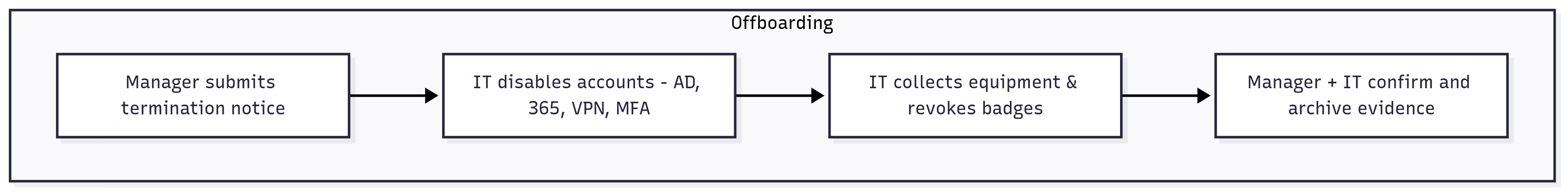

In IT terms, this is about managing user accounts, device authorizations, and process permissions. Every employee gets a unique username and password, devices are enrolled and validated (through Active Directory, Azure AD, or mobile device management systems), and automated processes (like software update services) are tied to approved accounts. Firewalls and access control lists (ACLs) enforce these rules at the network level. Without this discipline, old user accounts or rogue devices can quietly remain doorways into your systems, making it an easy target for attackers.

Examples:

- Employee offboarding: Sarah from accounting leaves the company. If her Active Directory account isn’t disabled the same day, she could still log in remotely to QuickBooks or email. Even if she never would, a hacker could discover her old account and brute-force the password, gaining unauthorized access. Proper access control means her account is promptly disabled and removed from all systems she used.

- Device control: A team member buys a new personal laptop and tries to connect it to the company SharePoint library that stores Federal Contract Information. Because the laptop isn’t enrolled in the company’s Intune management system, it’s automatically blocked. The employee requests approval, IT enrolls the device, and only then is access granted. This ensures unpatched or compromised devices can’t connect.

If you’d like done-for-you help, Opsfolio CaaS can provision and disable accounts, enforce Intune/AD policies, and maintain an auditable access log for you. If you prefer to manage it in-house, established tools from Microsoft (Active Directory, Intune), Okta, or JumpCloud can also support access control effectively.

Common mistakes:

- Leaving old user accounts active after employees leave

- Allowing personal laptops and phones to connect to company networks without vetting or management

Limit Access by Transaction and Function (AC.L1-b.1.ii)

What it means and why it matters: Picture your business as a workshop. Not everyone needs access to every tool. A new intern might only need scissors and tape, while a senior carpenter uses the table saw. If everyone had full access, accidents would be more likely and work would slow down. In the same way, your information systems should only give people access to the “tools” they actually need for their job. This prevents both honest mistakes and intentional misuse.

In IT terms, this is known as the principle of least privilege: users should be granted only the permissions they need to perform the tasks they are required to do. Systems like Active Directory, Microsoft 365, and QuickBooks support this by letting you define permissions by role. For example, you can allow a user to read data but not delete it, or to enter invoices but not approve payments.

These permission sets are called role-based access controls (RBAC), and they ensure employees only have the ability to perform the transactions and functions required. Done correctly, RBAC reduces the impact of malware, insider threats, or a compromised account, because attackers can’t escalate beyond the limits of the role.

Examples in practice:

- Finance vs. HR permissions: Your HR specialist needs access to employee files in SharePoint but has no reason to touch accounting data. Meanwhile, your finance lead uses QuickBooks to manage accounts but shouldn’t be able to open personnel files. By separating permissions, each department can work effectively without introducing unnecessary risks.

- Intern access control: A summer intern is hired to help clean up old documentation. You create a login that allows them to read and edit non-sensitive documents in a shared drive but blocks them from accessing the secure folder containing DoD contract data. This way, they can contribute to their project without risking exposure of FCI.

Common mistakes:

- Giving every employee “administrator” or “super-user” rights out of convenience

- Failing to remove elevated access when someone changes roles internally

Verify and Control External Connections (AC.L1-b.1.iii)

What it means and why it matters:

Your company network can be thought of as analogous to an office building. The main door might be secured, but what if employees start leaving windows open or sneaking in through the back alley? Those side entrances can undo all your security. External connections work the same way: if you don’t monitor and control them, sensitive government contract data (FCI) can slip out through unexpected channels.

From a technical perspective, “external systems” include any system you don’t fully control — personal laptops, home Wi-Fi, or third-party cloud services providing infrastructure or workload handling. This requirement means you must identify, verify, and limit these connections.

That includes enforcing Virtual Private Network (VPN) use for remote access, blocking unapproved devices with Mobile Device Management (MDM) tools, and setting policies for which cloud apps are allowed. Firewalls, conditional access policies, and endpoint certificates are the tools that ensure only trusted systems can connect.

Examples in practice:

- Remote work policy: Your company just won a DoD contract, and employees will work from home. One staff member tries to log into the contract portal from their personal laptop. Because the machine isn’t enrolled in company MDM, access is blocked. Instead, the employee is issued a company-managed laptop that enforces encryption, antivirus, and VPN use before connecting. This ensures only secure devices touch FCI.

- Cloud tool sprawl: A project manager wants to share files quickly via Dropbox, but the IT team reminds them that only the company’s approved Microsoft 365 cloud is authorized for storing FCI. By keeping contract data inside an approved, monitored platform, the business avoids data leaks and shows compliance with CMMC rules.

Common mistakes:

- Allowing staff to use personal laptops, phones, or cloud apps for contract work without verification

- failing to document which external systems are permitted

💡 For a deeper dive on secure remote access, see our step-by-step guide on implementing VDI with Azure and how it supports CMMC compliance.

Control Public Information (AC.L1-b.1.iv)

What it means and why it matters: Your company’s public-facing interfaces like its website or social media feed are like shop windows of a store. Whatever you put there can be seen by anyone walking by, including customers, competitors, or even attackers. If you accidentally leave sensitive documents in that window, you’ve exposed information that was never meant for the public. That’s why this requirement exists: to prevent Federal Contract Information (FCI) from slipping into places where anyone can view it.

Technically, this requirement is about managing and reviewing content before it goes onto publicly accessible systems, such as your website, press releases, blogs, or even file-sharing platforms. Organizations should establish who is allowed to post information, enforce a review process to check that no FCI is included, and have procedures for quickly removing anything posted by mistake. In practice, this looks like access restrictions on your content management system, documented approval workflows, and monitoring of public-facing systems.

Examples in practice:

- Press release oversight: Your marketing team drafts a press release about winning a DoD subcontract. The draft includes details about deliverables that came directly from the contract. Before it’s posted on the website, the company’s security officer reviews it and removes all references to FCI, approving a safer, high-level version. This ensures the announcement communicates the win without disclosing sensitive details.

- Website file posting: An employee uploads a PowerPoint presentation from a trade show onto the public site. During the review process, the IT team spots that one slide still contains a screenshot of a system with contract numbers and FCI. They reject the posting, edit the file to remove the sensitive material, and only then make it public.

Common mistakes:

- Allowing any employee to upload content to the website without review

- Failing to catch FCI embedded in presentations, screenshots, or attachments before they’re made public

Identify Users, Processes, and Devices (IA.L1-b.1.v)

What it means and why it matters:

Picture a gated community. Every resident has their own address, and every car has a license plate. Without these unique identifiers, you wouldn’t know who belongs and who doesn’t. Identification in cybersecurity works the same way: every person, process, and device needs its own “badge” so the system knows exactly who or what is requesting access.

In your systems, this means assigning unique identifiers such as usernames, device IDs, or service account names. In practice, this might be usernames in Active Directory, device identifiers managed by Mobile Device Management (MDM) tools, or unique IDs tied to network equipment like routers and printers. Service accounts (automated processes like software update tools) also need to be uniquely identified. Without this foundation, other safeguards like authentication (verifying identity with a password or MFA) and access control (limiting what someone can do) cannot work reliably.

Examples in practice:

- Employee identification: Your company sets up unique Office 365 accounts for every employee. Rather than sharing “admin@company.com,” each staff member logs in with their own email and username. When Maria from HR accesses SharePoint, the logs show her activity specifically, making it possible to trace issues back to the right person.

- Device identification: Your IT team uses Microsoft Intune to manage laptops. Each laptop is registered with a unique device ID. When an unregistered personal laptop tries to connect to the corporate Wi-Fi, it’s denied. Only devices on the approved list can access systems that contain Federal Contract Information (FCI).

Common mistakes: Allowing shared accounts for convenience (e.g., everyone logging into “frontdesk@company.com”), or failing to keep an updated inventory of devices, leaving unidentified machines on the network.

Authenticate Users, Processes, and Devices (IA.L1-b.1.vi)

What it means and why it matters:

A real-world analogy to understand this control is checking into a hotel. The front desk doesn’t just take your word for who you are. They ask for ID and a credit card before handing over the room key. The same principle applies to your company’s information systems: it’s not enough for someone (or something) to claim an identity; you must verify that identity before granting access. This safeguard prevents impostors from slipping in and protects your Federal Contract Information (FCI).

Technically, authentication is the verification step that comes after identification. Once a user, device, or process says “I am this account,” the system must confirm that claim. This is most often done with passwords, PINs, or multifactor authentication (MFA) for people. Devices use certificates, and processes use keys or tokens. A non-technical user might think of these similar to a house-key or a password, though the implementation is a bit more complicated.

Systems like Active Directory, Microsoft 365, and VPN gateways enforce these rules. A big risk is leaving devices or applications on their default factory passwords (like “admin/admin”), which are widely known and easy for attackers to exploit. Proper authentication ensures that only verified identities get in, not just anyone who knows the account name.

Examples in practice:

- Resetting default passwords: You buy a batch of new laptops for staff working on a DoD project. Out of the box, they ship with a default administrator username and password. Before issuing them, IT resets every default credential and assigns each employee a unique login. Without this step, an attacker could easily guess the factory-set password and break in.

- Cloud service login with MFA: Your company moves email to Microsoft 365. Each employee must log in with their unique username and password, and MFA is enabled. When John from engineering tries to sign in from home, he enters his password and then approves a push notification on his phone through his Authenticator app. This extra step ensures that even if his password were stolen, no one could log in without his phone.

Common mistakes:

- Leaving default credentials unchanged

- Failing to enforce authentication for all devices that access company systems

Sanitize or Destroy Media Containing FCI (MP.L1-b.1.vii)

What it means and why it matters:

Think of sensitive information like a note on paper with your credit card number. If you throw the note in the trash without shredding it, anyone could pick it up and read it and use the information to file an unauthorized charge. The same is true for digital media: old CDs, USB drives, laptops, and even office printers often store copies of Federal Contract Information (FCI) used during contracting engagements. If these devices are discarded or reused without properly cleaning them, you could unintentionally hand government data to whoever gets them next.

The technical way to address this is “media disposal.” This means sanitizing or destroying storage media before it leaves your control. This can include hard drives in laptops, memory in copiers, CDs, USB sticks, or even paper files. Sanitization may involve using disk-wiping software, cryptographic erasure, or degaussing (for magnetic drives). When reuse is safe and practical, media must be fully cleared of FCI before being redeployed. If secure erasure isn’t possible, the media should be physically destroyed via shredding, pulverizing, or incineration. Following NIST SP 800-88 guidelines for media sanitization is a recognized best practice.

Examples in practice:

- Office cleanup and old devices: During an office move, your staff discovers a box of old external hard drives from a retired server. Instead of throwing them away, IT logs each drive, uses NIST SP 800-88 compliant wiping software to clear the data, and generates a report of successful sanitization. The wiped drives are then recycled responsibly. This ensures no FCI leaves the company’s control in readable form.

- Printer replacement: Your company leases multifunction printers that scan and email documents. At the end of the lease, the vendor comes to pick up the old units. Before releasing them, IT staff confirm that the printer hard drives are wiped using the vendor’s certified sanitization process. They keep a certificate from the vendor stating the data was securely erased. This prevents scanned contract documents from being recovered later.

Common mistakes:

- Tossing old hard drives or USB sticks in the trash

- Assuming that deleting files is enough (simple deletion doesn’t remove the underlying data)

Limit Physical Access to Systems and Equipment (PE.L1-b.1.viii)

What it means and why it matters:

You lock the doors to your office every night. This is not just to keep people out of the building but also to protect the valuable items inside, like computers, files, and equipment. If anyone could walk in freely, they could steal information or tamper with your systems. For the same reason, you must restrict who can physically reach your information systems so only trusted, authorized people can get near them.

This means controlling access to spaces and devices that store or process Federal Contract Information (FCI). That includes server rooms, network closets, office spaces, and laptops. Controls can include door locks, keycards, security guards, or even locked cabinets for portable equipment. Limiting physical access is a critical part of cybersecurity because someone with physical control of a system can bypass many technical protections like firewalls or passwords. For example, plugging a malicious USB into an unlocked computer could compromise your entire network.

Examples in practice:

- Server room access: Your small business keeps a server in a supply closet that also houses cleaning supplies. Initially, everyone had the key, including contractors. To comply with CMMC, you install a keypad lock on the door, give access only to IT staff, and keep a record of who knows the code. Now, only authorized employees can get near the server that handles FCI.

- Laptop storage: An engineering team works on sensitive DoD drawings using laptops. To prevent theft, they store laptops in a locked cabinet each night when leaving the office. Only the project manager and assigned team members have the cabinet key. This ensures the devices aren’t left unattended and vulnerable to being stolen or tampered with.

Common mistakes:

- Leaving servers or networking equipment in open spaces where anyone could touch them

- Letting all employees share the same office keys without tracking who actually has access

Manage Visitors and Physical Access Devices (PE.L1-b.1.ix)

What it means and why it matters:

In your home, you don’t just let strangers wander in freely. You greet them, ask why they’re there, and keep an eye on them while they visit. You make sure they follow protocols like staying with the main guest party and only going to the bathroom on request, and staying out of your personal living area. You also track who has house keys, because giving out copies without oversight could put your family at risk. This is because your home has private information and belongings that could be compromised if a guest accessed them improperly.

The same concept applies to your contracting business: you must carefully manage visitors who enter spaces containing Federal Contract Information (FCI) and track who holds the “keys” to your systems.

This involves three parts: escorting visitors, monitoring their activity, and controlling physical access devices such as keys, keycards, and badges. Visitors must be logged when they arrive, wear badges that mark them as guests, and be supervised while in restricted areas. Physical access devices should be issued only to authorized staff, tracked, and promptly deactivated when no longer needed. Without these controls, visitors could accidentally (or intentionally) see sensitive data, and lost or unmanaged keys could provide ongoing unauthorized access.

Examples in practice:

- Visitor log and escorting: A contractor comes to repair your office’s HVAC system. Because the server room is in the same space, the contractor signs in at reception, receives a visitor badge, and is escorted by the facilities manager while the work is completed. Afterward, the badge is returned and the visit is logged. This ensures the contractor never has unsupervised access to systems storing FCI.

- Managing keycards: Your company issues electronic keycards to employees for office entry. An employee leaves the company, but instead of letting the card remain active, HR immediately notifies IT, who deactivates the card in the access control system. This prevents the former employee from reentering the building later, reducing risk of unauthorized physical access.

Common mistakes:

- Allowing guests to roam unsupervised

- Forgetting to deactivate keys and badges after guests leave

Monitor and Protect Network Boundaries (SC.L1-b.1.x)

What it means and why it matters:

Think of your network like an airport. Every person and bag has to go through security before entering the secure area. TSA agents don’t just let anyone walk through; they check IDs, scan bags, and stop anything suspicious. Security doesn’t stop absolutely everything: bags can get through because they serve a necessary function in travel. But they have to go through strict checks to make sure they’re safe.

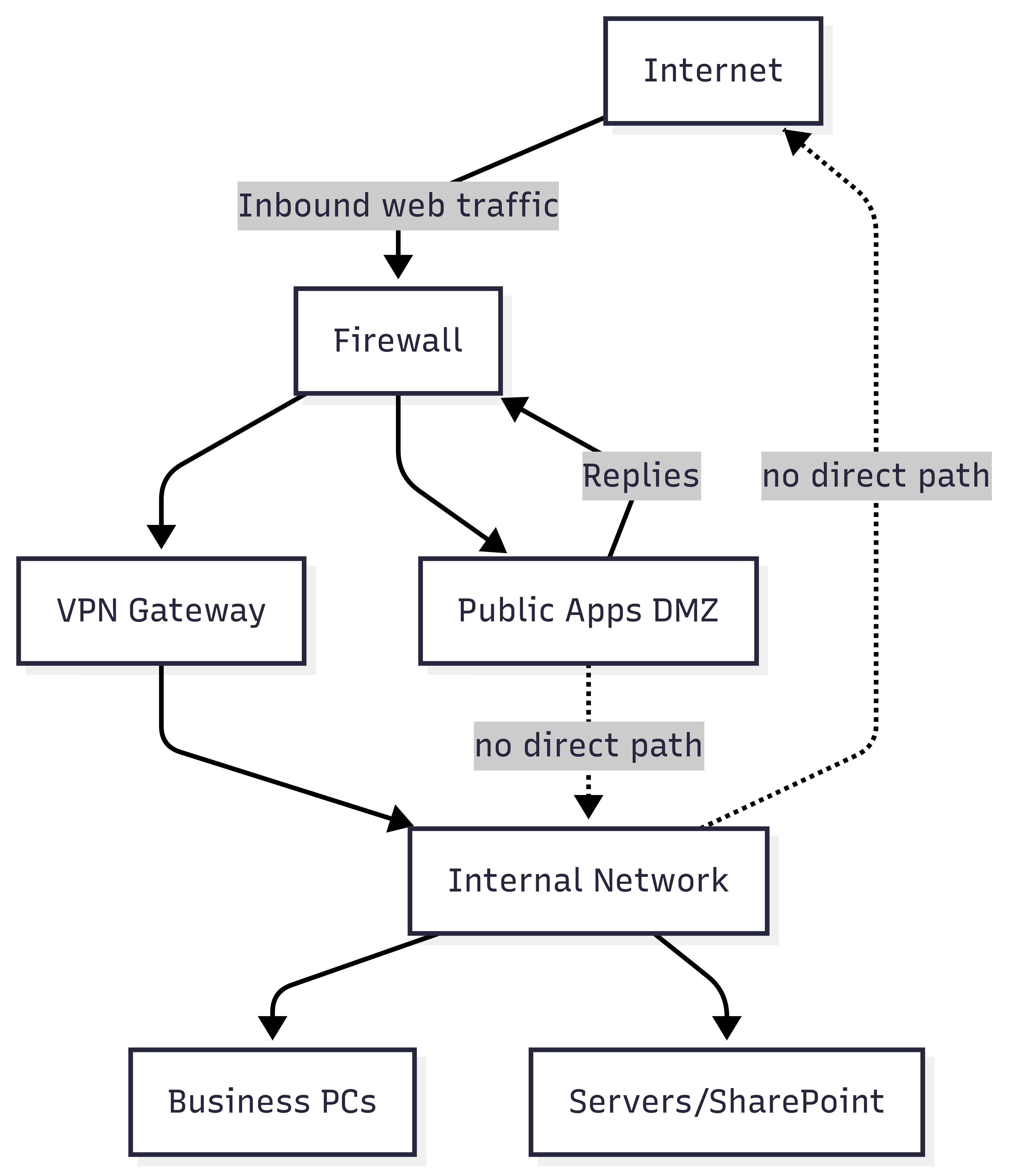

Your firewall and monitoring tools work the same way for your business. They inspect incoming and outgoing traffic, block dangerous items, and keep a log of who passed through. Without this checkpoint, harmful software or attackers could stroll right in.

In IT terms, this means defining both your external boundary (where your network touches the internet) and key internal boundaries (separations within your network, such as between development systems and production systems). Tools like firewalls, routers, intrusion detection systems, and proxies enforce these boundaries by monitoring, controlling, and protecting network traffic. For example, a firewall can block suspicious websites, while an intrusion detection system can alert you if someone is probing your servers. Boundary protection reduces the chance that malware, attackers, or even careless employees can cross into sensitive parts of your environment where Federal Contract Information (FCI) is stored.

Examples in practice:

- External firewall: Your company installs a firewall at the edge of its network that blocks all inbound internet traffic except for approved services like email. The firewall also prevents employees from accessing websites known for spreading malware. Each day, IT reviews logs that show what was blocked, helping them spot unusual activity. This keeps attackers from sneaking in through the public internet.

- Internal segmentation: An engineering team uses a separate lab network for testing new software. That lab is segmented from the main business network with a second firewall. Even if malware infected a lab computer, it couldn’t spread to systems holding FCI because of the internal boundary. This protects the sensitive contract data from accidental spillover during experiments.

Common mistakes:

- Running your entire office on one flat network without internal separation

- Failing to monitor firewall logs so malicious traffic goes unnoticed

Separate Public-Facing Systems from Internal Networks (SC.L1-b.1.xi)

What it means and why it matters:

Imagine a retail store: the showroom is open to the public, but the stockroom and cash office are kept off-limits. Customers can browse what’s on display, but they can’t walk into the back and access your inventory or financial records. The same principle applies in IT. Systems that anyone on the internet can reach, like your website, should never sit side-by-side with systems that hold sensitive government contract data.

In technical terms, this requirement is about separating public-facing systems from internal systems using a demilitarized zone (DMZ). Firewalls, VLANs (Virtual Local Area Networks), or cloud-based isolation are used to logically or physically separate these systems from your internal business network. This ensures that if a public system, like a website, gets hacked, the attacker can’t immediately jump into your network where Federal Contract Information (FCI) is stored. Proper network segmentation is a cornerstone of modern security design.

Examples in practice:

- Recruiting website separation: Your HR team wants to post job openings and accept applications online. Instead of hosting the job board on the same server as your internal HR files, IT places the public site in a DMZ subnet isolated by firewalls. Even if the job site is attacked, the internal HR systems remain shielded from exposure.

- Vendor portal isolation: A small contractor sets up a portal for subcontractors to upload invoices. Because the portal is accessible over the internet, IT configures it in Microsoft Azure on a separate virtual network with strict firewall rules. Internal systems that store DoD project data are placed on a different subnet, with no direct pathway from the public-facing portal.

Common mistakes:

- Hosting public websites or portals on the same network (or server) as sensitive internal systems

- Leaving firewall rules too open so public systems can still talk directly to the internal network

Identify, Report, and Correct Flaws (SI.L1-b.1.xii)

What it means and why it matters: The flaw remediation process in IT works much like in the auto industry. When a manufacturer discovers a safety flaw, they alert customers, fix the defect, and make sure the cars are safe to drive. If drivers ignored recall notices, accidents would become much more likely. The same principle applies to your business’s software and systems: flaws are discovered all the time and addressed by vendors. But you as the business owner still need to take advantage of the solutions put forward, and if you don’t fix the flaws quickly with the provided solutions, attackers can exploit the flaws to steal data or disrupt operations.

In IT terms, this requirement is about patch management and vulnerability remediation. Flaws in operating systems, applications, or firmware are identified through vendor alerts, vulnerability databases (like CVE), or scanning tools. Once identified, they must be reported to the responsible staff and corrected within a defined time frame. Correction usually means applying software patches, service packs, hotfixes, or configuration changes. Tools like Windows Update, WSUS, Linux package managers, or third-party patch management solutions help automate this process. Organizations should also define timelines (e.g., critical flaws fixed within 7 days, low-risk flaws within 30 days) so remediation is consistent and traceable.

Examples in practice:

- Weekly patch cycle: Your IT team sets a policy to check for Microsoft and Adobe updates every Friday. During one of these checks, they find a new patch for a critical vulnerability in Windows that hackers are already exploiting. They deploy the patch the same day across all laptops that handle Federal Contract Information (FCI). This closes the window of exposure before attackers can strike.

- Router firmware update: During a monthly review, the IT administrator sees that the office firewall has a new firmware update addressing a security weakness. They schedule downtime, install the update, and test the firewall afterward to ensure it’s still working properly. Without the update, attackers could have exploited the flaw to bypass the firewall and access FCI.

Common mistakes:

- Relying on automatic updates without checking they’ve applied successfully

- Leaving critical systems unpatched

Protect Against Malicious Code (SI.L1-b.1.xiii)

What it means and why it matters:

Malicious code can be deceptive, like termites in a wooden house. Everything might look fine from the outside as termites don’t affect the surface layer of the house. But once inside, termites eat away at the structure until it collapses. In the digital world, malicious code, like viruses, worms, spyware, Trojans, or ransomware, works the same way. Often, these programs operate under the radar without appearing like anything is wrong. Malware sneaks into your systems through email attachments, infected websites, or USB drives and then causes damage, steals data, or locks you out. Without proper defenses, Federal Contract Information (FCI) could be exposed or destroyed.

In IT terms, this requirement is about deploying anti-malware protections at the right places in your environment. These locations typically include workstations, servers, email gateways, web proxies, and mobile devices. Malicious code protections include antivirus software, endpoint detection and response (EDR), email filters, web filtering, and intrusion detection systems. These tools look for known malware signatures, suspicious behavior, or unsafe files and stop them before they can harm your systems. By placing these protections at system entry and exit points, you reduce the chance that infected files ever touch your internal network where FCI is stored.

Examples in practice:

- Email protection at the gateway: Your company’s email system has built-in antivirus and filtering turned on. When a subcontractor sends over a suspicious PDF, the system automatically checks it before it even reaches employees’ inboxes. Because the protection is active at the mail server level, the file is quarantined right away, and IT is alerted.

- Endpoint protection: A field engineer plugs in a personal USB drive to transfer photos but accidentally brings in malware. The antivirus software on the laptop immediately flags the suspicious files, blocks them from executing, and reports the incident. Without that protection, the malware could have spread to the shared drive containing DoD contract documents.

Common mistakes:

- Only installing antivirus on desktops while forgetting servers or mobile devices

- Relying on outdated free antivirus software that doesn’t cover modern threats

Keep Malicious Code Protection Updated (SI.L1-b.1.xiv)

What it means and why it matters:

Think of your antivirus like a vaccine. It protects you against known diseases, but when new strains emerge, you need booster shots to stay protected. Antivirus updates are those boosters. This software rely on up-to-date “signatures” and detection methods to spot the latest threats. If you don’t update these tools, they become blind to new types of malware, leaving your systems, and the Federal Contract Information (FCI) they hold, vulnerable.

In IT terms, this requirement means ensuring that all malicious code protection mechanisms (antivirus software, endpoint detection tools, email/web filters) are updated whenever new releases are available. Updates may include new virus signatures, improved scanning engines, or security patches that fix flaws in the protection software itself. Most modern tools can update automatically over the internet, but someone in your organization must ensure that these updates are actually happening. Without frequent updates, malware that was created yesterday could bypass defenses that worked perfectly last week.

Examples in practice:

- Automatic updates enabled: Your IT manager installs endpoint protection across all company laptops. They configure the system to download and apply updates every night. One morning, a newly released ransomware strain tries to infect the network. Because the antivirus had already received the updated signature overnight, the attack is detected and blocked automatically.

- Missed updates cause trouble: A small subcontractor keeps antivirus installed but disables automatic updates to avoid slowing down workstations. Months later, an employee downloads what looks like a harmless PDF but is actually new malware. The outdated antivirus doesn’t recognize it, and the system is compromised. The company learns the hard way that protection without updates is like locking your doors but leaving the windows open.

Common mistakes:

- Installing antivirus once and assuming it “just works” forever

- Turning off automatic updates

Perform System & File Scanning (SI.L1-b.1.xv)

What it means and why it matters: Imagine your office mailroom. Every incoming package gets opened or scanned before being distributed to employees. Most packages are harmless, but this step ensures that nothing dangerous or unexpected makes it to someone’s desk. File scanning works the same way for email attachments and downloads, inspecting them before they reach users.

In IT terms, this requirement means performing two kinds of scans:

- Real-time scans: files are checked automatically whenever they’re downloaded, opened, or executed.

- Periodic scans: scheduled sweeps of entire systems to look for malware that may have slipped in earlier.

Tools like antivirus software, endpoint detection and response (EDR) platforms, and email/web filters enforce this safeguard. Real-time protection is your first line of defense, while periodic scans act as a safety net, checking stored files against the latest threat intelligence.

Examples in practice:

- Email attachments scanning: A project manager receives a PDF from a subcontractor. As soon as the file is downloaded, the company’s endpoint protection scans it in real time and detects suspicious code. The file is quarantined before the employee can open it, preventing a malware infection.

- Scheduled system scans: Every Sunday night, the IT team configures laptops and servers to run full antivirus scans. During one scan, the software finds an old Excel file that had been infected with malware but wasn’t detected earlier. The tool quarantines the file and alerts IT, stopping the threat before it spreads to systems holding FCI.

Common mistakes:

- Turning off real-time scanning because it “slows things down”

- Assuming that files from trusted partners don’t need to be scanned

Malware Defense Stack

| Layer | Icon | What It Does |

|---|---|---|

| Email & Web Filters | 📧🌐 | Blocks malicious attachments & links before reaching inbox/browser |

| Firewall & Boundary Protection | 🛡️ | Filters inbound/outbound traffic; stops suspicious connections |

| Endpoint Protection (EDR/AV) | 💻 | Stops malware at devices; detects suspicious behavior |

| System & File Scanning | 🔍 | Real-time + scheduled scans catch hidden threats |

| Patch & Update Management | 🔧 | Fixes software flaws before attackers can exploit them |

Opsfolio CaaS can help you set up an automated patch cadence file scan reports automatically to your evidence vault. If you’d rather manage this in-house, established tools from vendors like Microsoft Defender, CrowdStrike, or Sophos provide robust scanning and protection options.

Building a Strong Foundation with Level 1

CMMC Level 1 may be labeled “basic safeguarding,” but as you’ve seen, these 15 practices cover the core habits that protect your business every day: controlling who gets in, managing devices, keeping systems patched, blocking malware, and locking both digital and physical doors.

For many SMB contractors, the hardest part isn’t the technology but the discipline of consistency and documentation. Assessors don’t just want to hear that you have antivirus or locks on the server closet; they want to see evidence that you maintain those controls and update them over time. If you build the routine now, you’ll not only pass a Level 1 assessment, but also prepare your business to grow into the more demanding requirements of Level 2.

Think of these 15 requirements as your baseline security hygiene: the digital equivalent of washing your hands, locking your office at night, and keeping receipts. They’re not glamorous, but they’re essential to protecting Federal Contract Information (FCI), keeping your contracts, and building trust with the Department of Defense.

You don’t have to tackle this checklist alone. While this guide gives you the concepts and examples, it’s not meant to cover every technical detail an assessor will check. Opsfolio CaaS delivers the full package, implementing these safeguards, collecting the right evidence, and keeping everything audit-ready so you can focus on your contracts, not compliance paperwork.

👉 Next steps: Review each practice against your current operations, gather evidence, and close any gaps. To find out about your CMMC preparedness status, take our free CMMC Self-Assessment. When you’re ready, we can guide you through readiness so you approach your CMMC journey with confidence.